I’ve spent the last couple of days photographing and uploading to my online shop a body of work which we fired back in June, but which we’ve been saving for a while. The pieces have been reduction fired in a gas kiln and the glazes are traditional type glazes such as celadon, chun and shino. There is one glaze in particular that is difficult to photograph and describe - my ‘delicate chun’ glaze. At first glance it is grey or white and very plain, but spend some time with it and you’ll see how it radiates a blue colour.

Teapot in ‘Delicate Chun’

This was one of the first recipes I mixed 10 years ago when I started experimenting with glazes, out of my trusty Emmanuel Cooper recipe book. But back then I only had an electric kiln and so it was used as a transparent glaze, sometimes layered over other glazes or a black slip for an opalescent effect. But now I am using it in reduction, it has revealed itself to me as a totally different beast - it is magic!

Let’s step back a moment and get to grips with the history of this glaze. According to Frank and Janet Hamer in their ‘Potter’s Dictionary’ (which I recommended on my reading list last week):

Jun (also known as chun). A pale blue, opalescent stoneware glaze named after a town in nothern China where it was first made in the 11th century. The jun glaze is related to the celadon glaze, being a feldspathic glaze on a buff body and firing in a reducing atmosphere.

But what makes this glaze so unusual and so different from nearly all the other glazes I work with is that the colour isn’t derived from a pigment, such an oxide, but from a trick of the light. I described it as magic. But it is science. Who cares - for me, science and magic often intermingle as I experience what I can only describe as a sense of awe.

Here’s the trick: The blue opalescence is caused by scattered light. The white light that enters the glaze surface is diffused by particles; the blue light is scattered back but the other light waves are absorbed by the clay body. This effect can be experienced best when the glaze is applied thickly and is even more obvious when layered over a dark slip or glaze.

Jenny Bowl in DC

The key to this trick is particle size, in particular, something called the ‘colloid’. This is a homogenous substance consisting of molecules or ultramicroscopic particles of one substance dispersed through a second substance. They are so tiny, these particles cannot be seen by the naked eye, even with a magnifying glass, but their collective qualities mean that they can create a visual effect (i.e. the blue colour in my chun glaze. )

One of my biggest questions when I came to write this post was, if this effect is created by particle size, why do I get a stronger experience with the blue light effect when I fire in reduction? It is to do with the colloid particles. In chun glazes, the colloid particles are nuclei of crystals, according to Hamer:

“phosphorous oxide, black iron oxide, calcium borate, titanium oxide, silica and devitrification of aluminosilicate from the body-glaze layer. Reduction helps to keep the phosphorous oxide isolated. It is also essential to incorporate the iron oxide in iron silicate nuclei which remain separate from the surrounding glass.”

Disclaimer: I’m not sure I totally understand all of that. But wood ashes contain varying substances depending on where the tree or plant grew, and so many contain both phosphorous and iron, which is why it is often used in chun. Interestingly, something which helps to answer my query about reduction, is that the nuclei of calcium borate and titanium oxide produce a different, longer ‘flush’ which can happen with or without reduction. It seems to be all about keeping the ultramicroscopic particles isolated in the glaze.

Detail shot of Autumnus Vase in Delicate Chun

Whilst I have been uploading my chun glazed pieces to the shop I have been pondering over how best to describe the colour. Pottery West being an online business but making tactile, hand-made and subtle objects is my biggest perpetual challenge. I notice how often the louder pieces sell quickly online, but the subtler pieces find homes at fairs and events. We have a need to see things with our own eyes, touch them. I have to work hard to be descriptive and take good photographs.

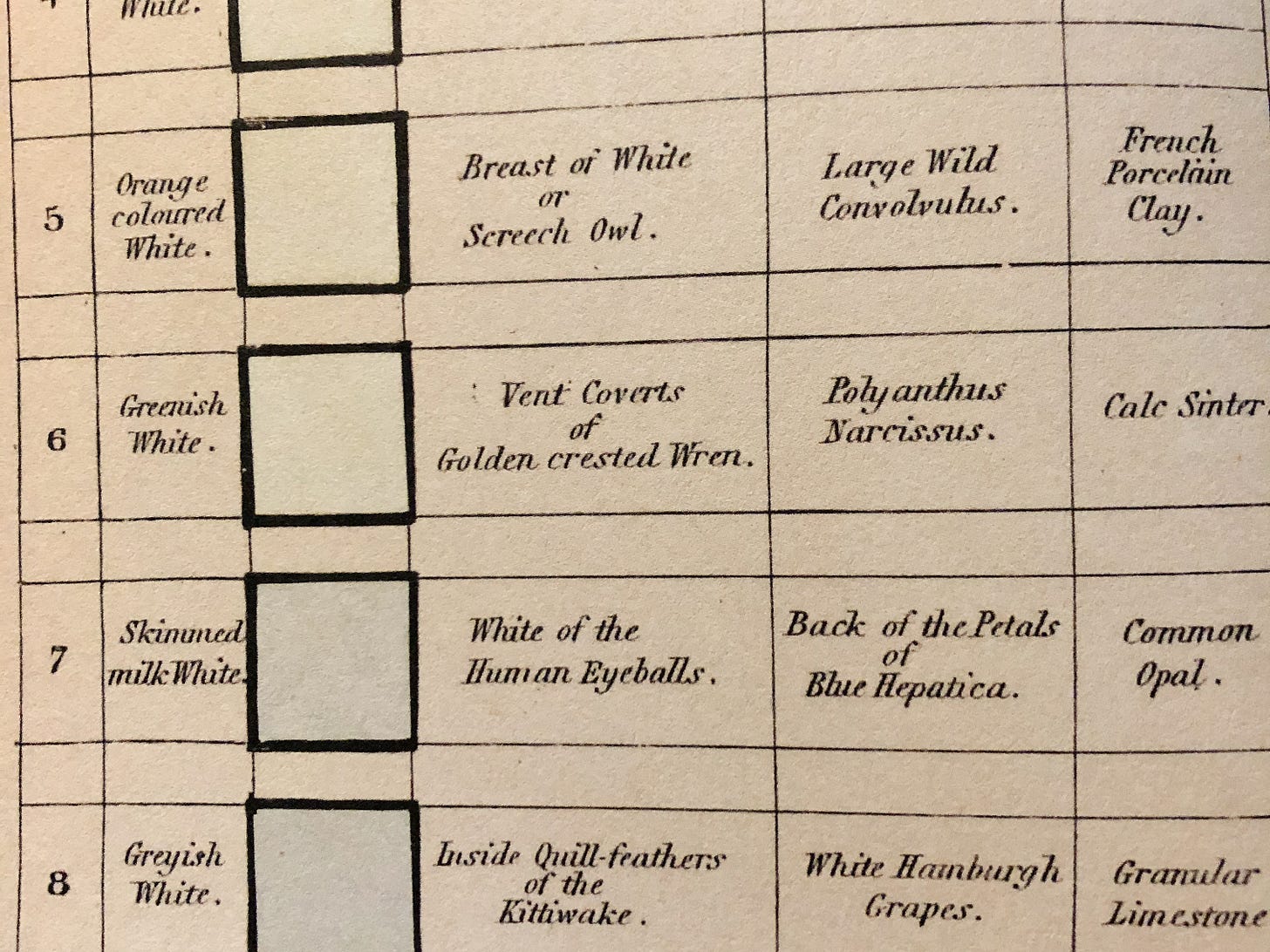

I thought it would be interesting to turn back to Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours, which I mentioned in my last post, and match the colour to one in there. Chemically, chun is similar to opal, and so I settled for Whites no. 7 ‘Skimmed milk White’ which is also described ‘White of the Human Eyeballs’. Despite Halloween being just around the corner I decided not to use this strangely accurate image in my product description! However maybe I should have used this:

Skimmed-milk White, is snow white, mixed with a little Berlin blue and ash grey.

Suggested Recipes:

Delicate Chun, Emmanuel Cooper, Cone 10, reduction and oxidation

Feldspar 46

Dolomite 6

Zinc oxide 6

Whiting 10

China clay 2

Flint 30

Derek Emms Jun, Cone 10, reduction and oxidation

Feldspar 43

China clay 1

Flint 30

Whiting 20

Talc 4

Colemanite 1

Black iron oxide 1